‘Mysticism’: The Centennial Year 1911-2011

Evelyn Underhill by Suzanne Schleck

In 1911 an unknown author published a 500 page book on the little known topic of mysticism. Accessible in its writing, it was nonetheless a work of scholarship, based as it was on some one thousand sources. The book was a huge success, and twelve editions appeared. Because its erudition, the suspicion was that the author, one Evelyn Underhill, must have been a male. Who else would have the academic training or ecclesiastical knowledge to produce such a work? In fact the author was a self-trained writer, wife of a London barrister, one who would go on to write or edit a total of thirty-nine books and some 350 articles and reviews. Underhill was poet, novelist, biographer and religious writer. Her single most important book was “Mysticism: A Study of the Nature and Development of Man’s spiritual Consciousness.” Everything which followed was contained therein in incipient form. The book has been in print continuously since its publication one hundred years ago. Its impact in the English-speaking world of religion has been great. The year 2011 is an opportunity to celebrate not only the gift of this seminal work, but the legacy of Evelyn Underhill—scholar, pioneer in the retreat movement, ecumenist, and spiritual director.

You are encouraged during this centennial year to initiate some event—large or small—to celebrate this contribution. If we can be of help in your planning, please be in touch at dgreen4@emory.edu. Now more than ever the world needs the wisdom of this extraordinary woman. Below find events planned.

Jan 10, 2011 “Evelyn Underhill: A Modern Guide to the Contemplative Life” Lecture by Dana Greene, Centre for Christian Spirituality, 1 Chapel Lane, Rosebank, Cape Town, South Africa, 7:30 p.m. Contact: www.christianspirit.co.za

Feb. 19, 2011 “Awakening in God’s Love, Exploring the Christian Spirituality of Evelyn Underhill “ Lecture by Dana Greene with Carl McColman. St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church, Atlanta, GA. Contact: http://imte.episcopalatlanta.org

March 11, 2011 “Anchored in God: A Quiet Day with Readings from Evelyn Underhill.” “Kathleen Staudt. Virginia Theological Seminary. See Fridays at the Seminary. Contact: www.vts.edu

March 2011 “Evelyn Underhill and the Mystic Tradition.” Rev. Dr. Jane Shaw. BBC Radio 3. Contact: www.gracecathedral.org

June 4, 2011 “Evelyn Underhill: Mysticism Revisited.” Co-sponsored by the Evelyn Underhill Association and the Center for Prayer and Pilgrimage, Washington National Cathedral. A Day with Bonnie Thurston, Kathleen Staudt, Carol Poston, Dana Greene, Todd Johnson. Contact: evelynunderhill@gmail.com

June 10-12, 2011 “A Celebration of Evelyn Underhill’s ‘Mysticism.’” The Retreat House at Pleshey, England. Contact: www.retreathousepleshey.com

September 10, 2011 “Evelyn Underhill: The Life and Work.” Lecture by Dana Greene St. Thomas Episcopal Church, Ft. Washington, PA. www.stthomaswhitemarsh.org

September 22-23, 2011 “100 Years of Women’s Scholarship in Mysticism and Spirituality.” The Center for Spirituality, St. Mary’s College, Notre Dame, IN Panel: Todd Johnson, Carol Poston, Dana Greene. Contact: http://www3.saintmarys.edu

TBA—“Evelyn Underhill” Grace Cathedral, San Francisco. Contact: www.gracecathedral.org

TBA—“The Legacy of Evelyn Underhill” Interview with Dana Greene. Spiritual World Net. Contact: www.spiritualworldnet.com

TBA—“Evelyn Underhill: Mysticism and Social Commitment”. Lecture by Susan Rakoczy, sponsored by the Pietermaritzbug Circle of Concerned African Women Theologians. Pietermaritzburg, South Africa.

News and Noteworthy: Scholarships and Resources

Two Canadian scholars have produced doctoral dissertations on Evelyn Underhill: Caroline Jean Rentz’s A Comparative Study of E. Underhill’s Criteria of Mysticism and C. G. Jung’s Theory of Individuation, University of Calgary, 1995, and Debra Joanne Jensen, Mysticism and Social Ethics: Feminist Reflections on Their Relationship in the Works of Evelyn Underhill, Simone Weil and Meister Eckhart, University of Toronto, 1995. Another dissertation is underway: Marie Crowley’s Beyond the Fringe of Speech: The Spirituality of Evelyn Underhill and Art. The Australian Catholic University.

John Francis’ article, “Evelyn Underhill’s Developing Spiritual Theology: A Discovery of Authentic Spiritual Life and the Place of Contemplation,” is forthcoming in Spring 2011 in The Anglican Theological Review.

The State University of New York Press has made available on demand Evelyn Underhill: Modern Guide to the Ancient Quest for the Holy.

Susan Rakoczy’s Great Mystics & Social Justice: Walking on the Two Feet of Love (Paulist Press) includes a chapter on Evelyn Underhill. Rakoczy’s article, “Mysticism and Social Commitment: Evelyn Underhill and Thomas Merton on Peace,” appeared in Magistra (Winter) 1996, Vol 2, iss. 2.

Miroslaw Kiwka published “Man and Mysticism in E. Underhill’s Approach” in Polish. An English abstract is available from mkiwka@pwt.wroc.pl.

Doreen Gildroy’s “Poetry and Mysticism” in American Poetry Review (May 1, 2010) contains material on Evelyn Underhill.

Michael Stoeber’s course, “The Spiritual Theology of Evelyn Underhill,” will be offered again in 2011. The 2009 syllabus is online at www.regiscollege.ca.

Tom Ryan’s “Evelyn Underhill on Spiritual Transformation: A Trinitarian Structure?” was published in The Australian EJournal of Theology, March 2007, Issue 9. Ryan’s “A Spirituality for Moral Responsibility? Evelyn Underhill Today” appeared in The Australian Catholic Record, 85, No. 2, 2008, pp. 148-61.

The 2nd Annual Interfaith Heroes Month honors persons who risked crossing religious boundaries to help heal the world. Evelyn Underhill is so honored in No. 16. See www.readthespirit.com/interfaith_heroes.

Four of Evelyn Underhill’s books are now availablease-books. See www.ebooks.ebookmall.com. Free online access is available to “Mysticism,” “Practical Mysticism” and “ The Spiritual Life.” Google timelines includes a timeline for the life of Evelyn Underhill. And Evelyn Underhill has now entered the quotable world. All of the following offer quotes from her, usually without citation: Brainy Quotes, World of Quotes, Quotes Daddy, Famous Quotes, Thinkexist.

Cory W. Devos lists his article “‘Fully Human, Fully Divine’: Integrating the Work of James Fowler and Evelyn Underhill.” at www.coreywdevos.com 2009.

Dana Greene was the presenter at the Annual Evelyn Underhill Quiet Day, 2010 at the Washington National Cathedral. The presentation, “Holiness: The Vocation of Every Christian,” explored Underhill’s insights into holiness, the capacity for God in each human being and the Christian mandate to be ‘vessels’ for the “redeeming, transforming, creative love of God.”

The Saints of God: Holy Women, Holy Men, the first complete revision of the Episcopal Church’s Lesser Feasts and Fasts, was released in July 2010. Evelyn Underhill continues to be listed on her death day, June 15th.

Evelyn Underhill is mentioned in two articles by Philip Sheldrake: “Christian Spirituality as a way of Living Publicly: A Dialectic of the Mystical and Prophetic” and “Spirituality and Social Change: Rebuilding the Human City.” Both appeared in Spiritus: A Journal of Christian Spirituality, Spring 1003 and Fall 2009.

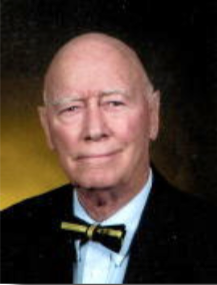

Coerper Honored

Rev. Milo Coerper, longtime Board member of the Evelyn Underhill Association, was honored at the EUA Quiet Day at the Washington National Cathedral for his service to the Association. Coerper, now eighty-five, has served EUA for more than two decades as its legal, fiduciary and sacramental mainstay. Kathleen Staudt replaces him as Association treasurer. Born in Milwaukee, Coerper is a graduate of the Naval Academy, the University of Michigan Law School, and Georgetown University from which he received a Ph. D in International Law. A man of many talents, Coerper was a partner in the international law firm Coudert Brothers, an Episcopal priest, a sailor, avid squash player, husband to Wendy, and father of three adult children. Deeply committed to Benedictine spirituality, he was an early member of the American Branch of the Fellowship, the Friends of St. Benedict, The Council of Friends of Canterbury Cathedral, Voluntary Chaplain at the Washington National Cathedral, as well as a Board member of the Shalem Institute for Spiritual Formation and a patron of the World Community for Christian Meditation. The Evelyn Underhill Association salutes Milo Coerper for his life work in forwarding the contemplative life among many Christian communities.

2011 Quiet Day of Reflection “Evelyn Underhill – Mysticism Revisited”

Saturday, June 4, 2011 Washington National Cathedral

Co-sponsored by the Evelyn Underhill Association and the Cathedral Center for Prayer and Pilgrimage, with Carol Poston, Dana Greene, Bonnie Thurston, Kathleen Staudt and Todd Johnson. In celebration of the 100th anniversary of Evelyn Underhill’s Mysticism, this gathering will offer reflections on what mysticism means for us today, and how Underhill’s work still speaks to our time. Beginning with a panel discussion in the morning, we will move into an afternoon of quiet reflection and guided meditation, helping us to experience how Underhill’s “practical mysticism” can illuminate our 21st century spiritual pilgrimage.

Saturday morning: A panel of scholars and teachers, including Carol Poston, Dana Greene, Kathleen Henderson Staudt and Todd Johnson will reflect on the importance of Underhill’s teaching about mysticism for our contemporary spiritual practice.

Saturday afternoon 1-5 “Quiet Afternoon” of Prayer and Reflection in honor of Evelyn Underhill, led by Bonnie Thurston. For more information contact: evelynunderhill@gmail.com.

“Keep a window open to Eternity.”

Evelyn Underhill

Where do homilies go once spoken?

Into thin air like smoke,

or deep down into the heart like a dagger?

Seldom does the preacher know

Last Sunday I preached.

My message, taken from Evelyn Underhill,

was that we “keep a window open to eternity.”

Upon going home a parishioner told her mom the message.

The mother, suffering from six brain tumors

and within days of death, responded:

“I’ll keep the window open if there is no draft.”

She died two days later, probably from a heavenly cold.”

Robert Morneau

Life as Prayer:

The Development of Evelyn Underhill’s Spirituality

by Todd E. Johnson

William K. and Delores S. Brehm Associate Professor of Worship, Theology and the Arts School of Theology

Although Evelyn Underhill (1875-1941) was baptized and confirmed in the Church of England, the Underhill family could be considered Christians in only the most social of terms. Underhill had little formal religious education and no theological training.a

In fact, Underhill’s first commitment to any sort of religious group was a hermetic sect known as the “Golden Dawn,” a most inauspicious beginning for one who would later be called “the spiritual director for her generation.”b

Underhill’s spiritual journey is a fascinating one, and one which has been well chronicled.c Underhill’s career began with her classic work Mysticism (1911)d and can be said to have concluded with her other classic Worship (1936).e These studies are similar in that they were comprehensive in their scope and pioneering in their approach, and both volumes are standard works in the fields of mysticism and liturgy. The fact that both remain in print is a testimony to their enduring quality. These works are very different in their theological approach however, as Mysticism is rooted in a hybrid of psychology, Neo-Platonism and evolutionary thought, while Worship is grounded in a Trinitarian theology centered on the Holy Spirit and a theology of sacrifice.

Between these two books Underhill accomplished numerous “firsts”: she was the first woman to lecture at an Oxford college in theology, the first woman to lecture Anglican clergy, and one of the first women to be included in Church of England commissions. These accomplishments along with her work as a theological editor, and her role as a spiritual director and retreat leader made Evelyn Underhill a prominent figure in her day.

One of the little understood facts of Underhill’s life and career are the changes of mind she went through over time. Underhill’s thought went through three distinct phases. Her earliest theological approach could be defined by a strong emphasis evolutionary thought, psychology and Platonic dualism. This period lasted from 1891-1919, and was dominated by writings on mysticism and mystical theology. Her rather optimistic theology was unable to explain the cruel realities of World War I. So in 1920 she began receiving spiritual direction from Baron Friedrich von Hügel, one of the most respected theologians in Europe at that time. This began a decade long theme of more Christocentric thought and a growing balance between God’s immanence and transcendence, which lasted from 1920-1929. The last years of her life (1930-1941) were marked by yet another paradigm shift, where under the influence of Russian Orthodox immigrants to England, Underhill’s theology took a firm shift to the third person of the trinity. Her development of a pneumatology happened coincidentally with her growing social conscience as expressed by her pacifism at the on-set of World War II.f

In terms of Underhill’s understanding of spirituality, it is notable is that over time Underhill shifts from the term “mysticism” that so dominated her early years as an author, to terms such as “life of the Spirit,” “the spiritual life,” and “spirituality.” Only twice in the late 1920s does Underhill write on mysticism, and from 1930 on her writings are almost exclusively on spirituality and worship. It would be interesting to see if Underhill’s use of the term spirituality was reflective of the use of that term by others, either past or present, or if (as I am inclined to believe), that her use of the term in fact, popularized the term “spirituality” for the second half of the century.

Underhill’s writings on what we would now call “spirituality” are bracketed by two works, Mysticism (1911) and The Spiritual Life (1937).g The first Mysticism can be understood well by reflecting on its subtitle, “A Study of the Nature and Development of Man’s Spiritual Consciousness.” This was a book describing the human potential of ascent to the divine. Underhill uses the classic three-fold paradigm of mystical union of purgation, illumination, and unification, but expands it adding two more stages. The result was her five-step process of conversion, purgation, illumination, surrender, and union. Underhill added a step at the very beginning, that being conversion, or a threshold of awareness of the ultimate reality (God) existing outside oneself. She also added a fourth step, conversion, which she drew from many mystical writings, but St. John of the Cross in particular. This stage was the “dark night of the soul,” that period dryness that tests one’s ultimate commitment to their spiritual journey. Underhill’s massive study, though heavily weighted towards medieval Christian mysticism was intentionally interreligious. Her goal was to demonstrate the universal human capacity for mystical accent to “reality,” that is, the more real supernatural world that is the goal of human existence. Though some saints and mystics might attain such a state of union with God in this world, most must wait for the life in the world beyond this world. Regardless, the journey was an inward and private one, what Plotinus described and the “flight of the alone to the One.”

The small volume The Spiritual Life was very different. This little book was a compilation of four radio broadcasts Underhill delivered on the BBC. Gone were the concepts of mystical union and human ascent. In their place was a three-fold pattern of the spiritual life: Adoration, Adherence and Cooperation. This pattern was derived from the French school of spirituality identified with Pierre de Berulle and Jean-Jacques Olier. This was an approach to the spiritual life that began with God’s initiative and resulted in a life conformed to the cruciform posture of our Lord. It also involved community and service to others. Gone was the philosophy and psychology of Mysticism, in its place was the Christian life of worship, prayer and ministry.

In her review of this book in Theology, Aelfrida Tillyard wrote this description of Underhill’s broadcasts, some of her last public presentations, “When Evelyn Underhill sat at the accordance, and sent her voice across space to thousands of unseen listeners, her heart must have been full of true apostolic zeal and the love of souls. She was not there to display her knowledge of German metaphysics, or the extent of her acquaintance great and small. She was not there to impress anyone with her grasp of psychological theories involved in spiritual exercises and systems of meditation. She was there to bring human beings in touch with their Creator, and, please God, she would do it, if she could.”h Underhill at the end of her life was passionately proclaiming a corrected understanding of prayer from her more famous mystical writings.

This essay is not intended to be an exercise in either the history of spirituality or spiritual autobiography. Instead my hope is to focus on a unique aspect of Underhill’s understanding of prayer and through it her changing understanding of the life of the Spirit. To do this I will focus on two essays written by Underhill in the late 1920s which indicate the time of a shift in Underhill’s thought and will high-light the importance of her newfound understanding of prayer. It also may provide a sounding board for you to consider your own theology of prayer and definition of Christian spirituality.

The first essay was actually a pamphlet published for the YWCA in England in 1926, simply entitled “Prayer.”i Although this work still has overtones of Underhill’s early mystical writings, such as an emphasis on God’s immanence, human effort in prayer, and the solitary nature of prayer. Yet there was a different feel to it than writings a decade earlier. This was more Christ-centered and less esoteric.

Underhill began by describing prayer as a broad genre rather than a single item, prayer is not “’simply’ this or that, (that would) spoil our understanding of (prayers) richness and variety.” Still Underhill does define the life of prayer as “our whole life towards heaven,” and no matter what type of prayer you pray, it is communion with God. Underhill continues to stress the work of prayer here though, asserting that “real prayer is a great and difficult art.”j

Underhill offers a metaphor for the spiritual life, that is the life of a healthy body. A healthy spirit, like a healthy body, must have food, fresh air and exercise to thrive. So it is in the spiritual life, one must have food, that is a steady diet of scripture reading and spiritual classics, have fresh air that is to live with an attitude of praise and gratitude, and finally exercise. Spiritual exercises require a disciplined routine; not simply reading praising and praying when one feels like it. Quoting St. Francis de Sales, “We seldom do well what we only do seldom.”k Fulfilling these three regimens is not the spiritual life, but prepares one for it. For the spiritual life is adoration and adherence. Adoration is the attitude which places God in the center of one’s life and not one’s self. Adherence is being passionately devoted to your relationship with God to the point where it takes precedence over all other things. It is ultimately, to live every moment with the recognition that you are in the intimate presence of God.

Though this is a significant move in Underhill’s thought, it still ends primarily in the spiritual life being an autonomous relationship (though guided by people of faith past and present) with God. There is little social support, intimacy or relevance for prayer, beyond one’s own spiritual self-improvement. This is not quite where Underhill ends up at the end of her life. Baron von Hügel diagnosed this tendency towards inwardness under his spiritual direction a few years earlier. His treatment was for Underhill to spend time caring for the poor. The seeds planted by von Hügel appear to have sprouted shortly after writing this tract, as we will see in her next essay.

In 1928 Underhill was invited to address the United Free Church in Scotland, and the topic she was given was prayer. Her address was not published until five years after her death in her Collected Papers.l This address is the first indication that Underhill’s theology of prayer had taken on a decidedly different tone. The first mark of distinction is the way that Underhill began her address when defining prayer. “What, then, is Prayer? In a most general sense, it is the intercourse of our little human souls with God. Therefore it includes all the work done by God Himself through, in, and with souls which are self-given to Him in prayer…. Prayer, then, is a purely spiritual activity; and its real doer is God Himself, the one inciter and mover of our souls.”m Although there is still an emphasis on God’s immanence it is tempered. More striking in this essay, as the quote above demonstrates, is a tempering of human will and action with God’s initiative and provision. In a word, prayer begins with grace and not works.

Of the three-fold pattern of the French school of Adoration, Adherence and Cooperation, Underhill had introduced the first two elements in her essay of 1926. This essay would be the one in which she completes the triad by introducing cooperation. Although she does not used the term cooperation per se. The entire essay is about prayer as the process of releasing yourself to do the will of God in the world. This is the life of prayer.

Underhill stresses in this essay a new theme that will become a common theme for the rest of her life: sacrifice. Prayer requires “self-given” souls in a spirit of sacrifice and oblation. The love of God that inspires us to prayer in the first place, is the love of our crucified Lord—self-sacrificial love. Underhill continues, “Self-offering, loving, unconditional and courageous, is therefore the first requirement of true intercessory prayer.”n Such an intercession operates on the supernatural plane, where the human spirit invokes God’s Spirit to act. But it also works on the human plane where the intercessor enacts one’s prayer in deeds of kindness, compassion, justice and mercy.

In what I consider to be one of Underhill’s most revealing and poignant prose, she wrote, “A real man or woman of prayer, then, should be a live wire, a link between God’s grace and the world that needs it. In so far as you have given your lives to God, you have offered yourselves, without conditions, as transmitters of His saving and enabling love: and the will and love, the emotional drive, which you thus consecrate to God’s purposes, can actually do work on supernatural levels for those for whom you are called upon to pray.”o

Prayer from this point on in Underhill’s writings had a decidedly social and, in the above sense, intercessory cast to it, as did Underhill’s life. She became much more conscious of the effects of sin in the larger world, not simply the individual life. The foremost example of this was her public advocacy of pacifism at the advent of World War II, a decidedly unpopular position and one that cost her reputation dearly. Still Underhill was unswerving. Her life of prayer had lead her to believe that Christian should kill another Christian for the sake of no nation, and if all baptized should refuse to fight there would be no war.

Few people have studied prayer in theory and practice—Christian and non-Christian—to the extent the Evelyn Underhill had. At the end of her life, after having considered many options, she concluded that prayer was about availing one’s self to the purposes of God, not invoking the activity of God for either spiritual assurance or earthly benefit, but for conformity to the life and ministry of the one through whom we pray, Jesus Christ the crucified.

In the spiritual bookshelves of our day, this understanding is not a big seller. Underhill’s early writings are those most frequently reprinted, and her later writings more difficult to find. Yet in the world today, what sort of woman or man of prayer would God ask us to be, one who strives for spiritual development alone, or one who offers their lives as living intercessions, empowered by the Spirit, sent by Christ, to do God’s will? Might the latter define all of our lives of prayer.

*Appeared in Fuller Theology, News & Notes. Vol. 56, No 2, Fall 2009. 16-19.

Endnotes

a Dana Greene, Evelyn Underhill: Artist of the Infinite Life (New York: Crossroad, 1990), 11-12.

b See Jonathan Bodgener, “Evelyn Underhill: Spiritual Director to Her Generation,” London Quarterly and Holborn Review 183 (1958): 46-50.

c Three biographies on Underhill have been published, and one incomplete manuscript remains unpublished. These are: Dana Greene, Evelyn Underhill: Artist of the Infinite Life; Christopher Armstrong, Evelyn Underhill: An Introduction to Her Life and Writings (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1975); Margret Cropper, Evelyn Underhill (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1958); and Lucy Menzies, “Biography of Evelyn Underhill,” TMs unfinished, Underhill Collection Archives: St. Andrews University Library, St. Andrews, Scotland. By far the most accessible and more important of these works is Greene’s study.

d Evelyn Underhill, Mysticism. A Study of the Nature and Development of Man’s Spiritual Consciousness, 1st ed. (London: Methuen and Co., 1911).

e Evelyn Underhill, Worship. Library of Constructive Theology, 1st ed. (London: Nisbet, 1936).

f For a more detailed survey of the development of Underhill’s thought see Todd E. Johnson, “Anglican Writers at Century’s End: An Evelyn Underhill Primer” Anglican Theological Review 80 (1998).

g Evelyn Underhill, The Spiritual Life. Four Broadcast Talks (London: Hodder and Stroughton, 1937).

h Aelfrida Tillyard, review of Evelyn Underhill, The Spiritual Life, Theology 34 (1937), p. 379.

i Evelyn Underhill, “Prayer,” in Evelyn Underhill: Modern Guide to the Ancient Quest for the Holy, ed. Dana Greene. (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1988) pp. 135-44.

j Underhill, “Prayer,” pp. 135-36.

k Underhill, “Prayer,” pp. 139.

l Evelyn Underhill, “Life as Prayer” in Collected Papers of Evelyn Underhill, ed. Lucy Menzies (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1946), pp. 61-72.

m Underhill, “Life as Prayer,” pp. 61-62.

n Underhill, “Life as Prayer,” p. 68.

o Underhill, “Life as Prayer,” p. 62.

Clarification

In her preface to her 1921-22 Upton Lecturers given at Manchester College, Oxford, Evelyn Underhill writes to thank the members of “the Oxford Faculty of Theology, to whom I owe the great honour of being the first woman lecturer in religion to appear in the University list.” In those years Manchester College was located in Oxford but was not a constitute part of Oxford University; its degrees were awarded through the University of London. Nonetheless as a major lecture Underhill’s presentations were listed on the Oxford University list of lectures given both by Oxford faculty and visiting, outside lecturers. Underhill could appropriately claim to be the first women lecturer in religion to appear on the Oxford University list.

How to Contact the Association

Feel free to contact us with questions, comments, contributions, new ideas.

EUA President

Dana Greene dgreen4@emory.edu

EUA Vice President

Merrill Carrington mcarrington@erols.com

Secretary

Missy Daniel mdaniel@religionethics.com

Charitable Contributions

Kathleen Staudt kathleen.staudt@gmail.com 9309 Greyrock Road

Silver Spring MD 20910

Newsletter Submissions

Dana Greene dgreen4@emory.edu

Purpose of the Association

The Evelyn Underhill Association exists to promote interest in the life and work of Evelyn Underhill. Each year the Association sponsors a Day of Quiet at the Washington National Cathedral, publishes an online newsletter, supports the work of archives at King’s College, London and the Virginia Theological Seminary, Alexandria, VA, and supplies answers to queries.

Donations

Donations may be sent to:

Kathleen Staudt

kathleen.staudt@gmail.com

9309 Greyrock Road

Silver Spring MD 20910